The plan to build social and affordable housing at the former racetrack hinges on $1.4 billion in financing. Can the Plante administration convince private developers to buy into that?

Article content

Hailed as bold and daring, the city’s plan to build thousands of social and affordable housing units in the Hippodrome sector hinges on a $1.4-billion question mark.

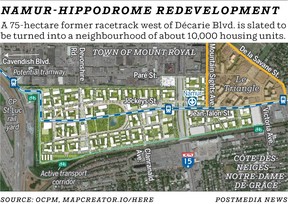

That is what the city estimates it will cost to build public infrastructure like water access, roads, sewers and sidewalks in the area of the abandoned Blue Bonnets racetrack several hundred metres west of the intersection of Jean-Talon St. and Décarie Blvd. After decades of delays, there finally appears to be momentum to develop the lot of land abandoned when Blue Bonnets closed in 2009. We take a look at some of the key questions that must be answered.

Advertisement 2

Story continues below

Article content

Who does the land belong to?

Owned by the province since the 1990s, the city was ceded the land in 2017 on the condition that it work quickly to turn the sector into a housing development, with a five-year timeline set for the first building permits to be issued.

Why did it take so long to get to this point?

The sticking point has always been the sheer amount of upfront investment needed by the city to build the water and sewer access as well as the roads and sewers. The most recent estimate from the city, dating back roughly two years, pegged the price tag at $1.4 billion. Michel Leblanc, the president of the Chamber of Commerce of Greater Montreal, points out that the city’s current level of indebtedness makes it prohibitive to borrow that amount of money upfront, so other partners and a new business model are needed.

It is for that reason that the city created a committee called GALOPH, made up of business leaders, government actors and non-profit corporations, in order to put together a business plan for the development.

You ask yourselves: ‘Why have things never started in the last few decades?” GALOPH president Pierre Boivin said during the news conference to unveil the city’s master plan for the Hippodrome-Namur sector recently. “There are many reasons, but that is certainly one of them, the impossibility of bringing infrastructure.”

Advertisement 3

Story continues below

Article content

Will there be an element of housing for those in need built in the sector?

The project consists of two parts: Namur — close to the Namur métro station, and Hippodrome — where the old racetrack sat. The city intends for 20,000 housing units to be built within the new neighbourhood, split evenly between Namur and Hippodrome. The Hippodrome sector’s 10,000 units, where there are currently no roads or sewers, will be comprised 100 per cent of what the city calls non-speculative housing, which includes social housing units subsidized by the government, affordable housing units sold or rented at a rate below the average market value, and housing units built and/or operated by co-operatives.

Will the project address the needs of families too?

Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante has said the development will include “a mixity” of housing that will accommodate single families and will be universally accessible, for those with mobility issues. The documentation describes a minimum of 4 floors per building. The neighbourhood will also have schools, a library, health-care institutions, a public square and an outdoor marketplace.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Story continues below

Article content

Is the city’s plan realistic?

It depends on who you ask. Leblanc said the plan requires buy-in from the business community, which he said is impossible to gauge at this point, because it’s a model of development that has never been tried before. Up to this point, building developers were eager to build in order to take advantage of the increase in real estate value of the neighbourhood. That incentive doesn’t exist in a model that is made up of 100-per-cent non-market-based housing, so the city will have to come up with a new way for private investors to make money on the deal.

A call for proposals issued by the city last year elicited no takers from the private sector.

Annick Germain, the director of urban studies program at Institut national de la recherche scientifique, said the key will be to start with development in the Namur sector, which is more realistic.

“I think it’s a very very long-term project. We need a strategy, but we should start with a very small part to at least start something quickly, and not wait 20 years before anything happens,” Germain said.

Isabelle Melançon, the CEO of the Institut de développement urbain du Québec agreed. She’s also a member of the GALOPH committee, and said there is a need to developing housing in all forms, because the housing crisis has seen demand surge for every type of housing.

Advertisement 5

Story continues below

Article content

“We have to offer Montrealers every kind of housing that’s possible, because everything is in short supply: condos, rentals, affordable and social. Everything is lacking.”

She added that contractors are eager to begin projects.

Where will the money come from to pay for the roads and sewers?

This question is still up in the air.

During the unveiling of the master plan for the sector in April, Plante said she remains optimistic that the city will be able to find partners with the private sector and the provincial and federal governments, and the non-profit sector, all of them represented on GALOPH.

“The city is not alone,” Plante said at city hall. “We’re surrounded by the private sector, builders, non-profit foundations that build as well, and other levels of government. It is a lot of money that has to be involved.”

At the same news conference, Boivin said he’s optimistic about the participation of the Canada Infrastructure Bank, which has so far pledged $2 million for studies. He hopes that means the federal agency will also chip in to help build infrastructure once a business plan has been presented.

Advertisement 6

Story continues below

Article content

But observers say it’s highly unlikely governments will subsidize the entire $1.4-billion-plus cost of building the infrastructure.

Typically when a new development is undertaken, the City of Montreal pays for the roads and sewers upfront with a borrowing bylaw and recoups that money with tax revenue that comes from the developments. In the case of the Hippodrome, however, this isn’t possible because of the sheer amount of debt the city would need to take on.

Leblanc believes the best way forward is to obtain some provincial and federal subsidies, and to fund the rest by creating a non-profit group that would take out the loans needed. The loans would have to be guaranteed by the provincial or federal governments, since the city can’t add to its debt load. The city would then share a percentage of the property tax revenue from the buildings built in that neighbourhood.

Leblanc said the city has not been open to this type of arrangement in the past, but that seems to have changed in the last year or so. At issue now appears to be the percentage the city is willing to share.

Advertisement 7

Story continues below

Article content

“In our analysis, if it’s 25 per cent, it won’t happen; if it’s 35 to 40 per cent it might happen,” Leblanc said.

The area is already heavily congested with cars. Is there a plan to manage traffic in the area?

It is already well known that the Décarie-Jean-Talon area is one of the worst intersections in the city. The plan for the Hippodrome development calls for a development that is less reliant on cars, with just one parking spot for every four homes. However, with 20,000 units planned, that still means thousands of cars. Add to that the planned developments of Mid-Town in St-Laurent and Royalmount in Town of Mount Royal and it’s a recipe for monster congestion.

“This is the worst location in the city to build anything because it’s already an area very congested and constrained,” Germain said.

The city’s plans call for a tramway to be built on an extended Jean-Talon St., which will run to Cavendish Blvd. once built. That leaves the problem of north-south traffic. Local mayors and other activists have called on the city to revive the Cavendish extension to extend the boulevard in both St-Laurent and Côte-St-Luc in order to meet at Royalmount Ave. Such an urban boulevard would give commuters an alternative to taking Décarie to transit from north to south in the sector. Plante has said she’s open to moving forward with the Cavendish extension, but not in the project’s first phase. The extension of Jean-Talon St. will be completed in that first phase, then construction of housing will begin.

Recommended from Editorial

Advertisement 8

Story continues below

Article content

Article content

Comments