Test your knowledge about Montreal’s iconic landmark as it celebrates its centennial.

Article content

The Mount Royal cross is turning 100.

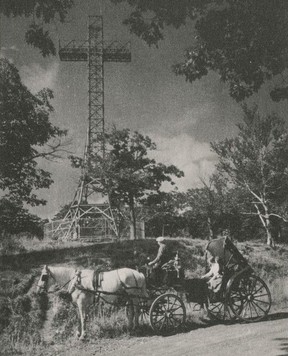

The iconic Montreal symbol was born in 1924. That year, the cornerstone was blessed on June 24, St-Jean-Baptiste Day, with construction completed on Sept. 15. It was first illuminated on Christmas Eve.

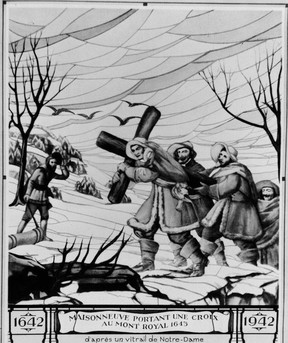

You may know that the metal structure commemorates a small wooden cross erected on the mountain by Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve in 1643 — and a 30-foot-high one Jacques Cartier put up in Gaspé in 1534.

Advertisement 2

Story continues below

Article content

But here are 10 things you might not have heard:

1. Children raised $10,000 to build it

A mountain cross was first proposed in a St-Jean-Baptiste Day sermon in 1874 by a Sulpician priest named Alexandre-Marie Deschamps.

He wanted to commemorate the cross that Maisonneuve, co-founder of Montreal, erected in the 17th century to thank God for sparing Montreal from a flood. The cross is a Christian symbol, recalling the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

The idea lay dormant for 50 years.

In 1924, the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal resurrected it. The SSJB, a nationalist group, launched a major fundraising campaign, with tens of thousands of children selling souvenir stamps at a nickel apiece. They raised $10,000. The cross is said to have cost $25,000.

2. It was supposed to feature observatories

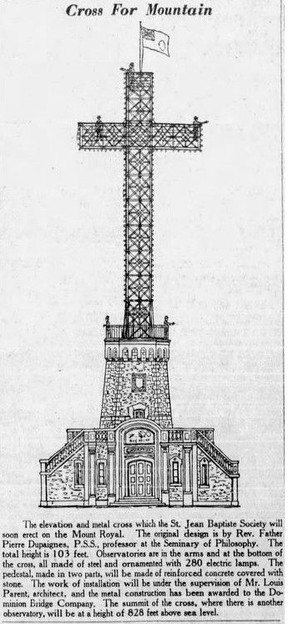

The SSJB commissioned Sulpician priest Pierre Dupaigne to design the cross. His plans included a stone pavilion that would serve as a base, with elevated lookouts for visitors.

A drawing published by the Montreal Star in June 1924 shows people on observatories at the base, in the arms and at the top of the cross. A staircase in the vertical part of the cross would lead people up.

Advertisement 3

Story continues below

Article content

In the end, only the 33-metre-high steel structure was built. When lit up, it can be seen from 80 kilometres away.

3. The designer didn’t like the final product

Dupaigne, a French-born professor at Montreal’s Séminaire de philosophie, was miffed that his dream cross never materialized.

Yes, the lit-up cross was beautiful at night, he said in a 1950 interview with Le Petit Journal.

But the structure “lacks body because the bars that make it up are too thin, giving it the transparent look of Meccano,” Dupaigne complained, referring to toy model construction sets.

“Moreover, its apparent proportions are distorted, making it appear too tall for its width and apparent size. … This aspect justifies the descriptions of crow perch, ugly Meccano and empty carcass that have been given to it.”

4. It’s a symbol of francophone nationalism

Erected as Quebec nationalism was flourishing, the cross was a symbol of the advancement of francophones in a city whose economy was traditionally dominated by the English-speaking elite.

“In the same way that a flag is planted on a stronghold, the erection of a large cross conceived as a symbol of French-Canadian national resistance atop Mount Royal represents the conquest of a physical and symbolic space that makes it possible to affirm that Montreal is above all a Catholic and French city,” historian Gaston Côté wrote in a 2006 paper.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Story continues below

Article content

“It’s not just Mount Royal Park that is claimed for French speakers, but the entire city.”

Yet the cross was backed by many anglophones, including Protestants.

In April 1924, The Gazette published a letter — signed “A Protestant” — welcoming the new landmark. “It is our Cross, it represents our greatest sacrifice, and we are going to place it on our highest site where all our new-home seekers will see it as they sail up the wonderful river. What hopes it will inspire, representing the loving, gentle Saviour.”

A month earlier, a Gazette editorial concluded: “Long may it stand, to be to Catholic and Protestant, old and young, native and newcomer, a beckoning finger by day and a veritable pillar of fire by night.”

5. Vandals, pranksters and activists love it

Jokers once arranged the lights to spell T-I-L-T, part of a “series of night-time pranks, from blacking out the cross altogether to spelling out four-letter words with a few well-chosen bulbs,” the Montreal Star reported in 1973.

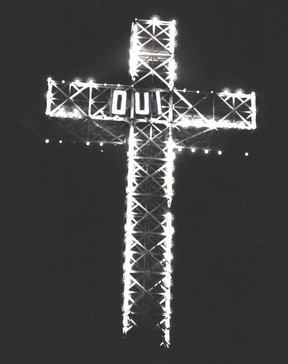

Separatists attached a “Oui” sign to the cross during the 1980 sovereignty referendum. Twelve years later, the Mouvement Souverainiste du Québec draped a giant “Non” banner on the structure to protest against the Charlottetown constitutional accord.

Advertisement 5

Story continues below

Article content

In 2012, a huge red flag was tied to the cross, referencing the red square that symbolized student unrest over university tuition fees.

Two years later, Greenpeace activists covered the structure with banners demanding justice for the boreal forest.

6. It changes colour

Normally white, the cross is a chameleon, its colour changing for special occasions.

The lights have burned purple for the death of pontiffs, including Pope Pius XII in 1958 and Pope John Paul II in 2005. Purple was also the colour of choice when King George V died in 1936 and upon the death of King George VI in 1952.

In 1975, it was blue in celebration of St-Jean-Baptiste Day. In the early 1980s, it turned red to mark a march against AIDS.

Initially, the cross featured 240 75-watt bulbs. In 1957, the city installed a new system that would cost less to run — 158 bulbs of only 50 watts.

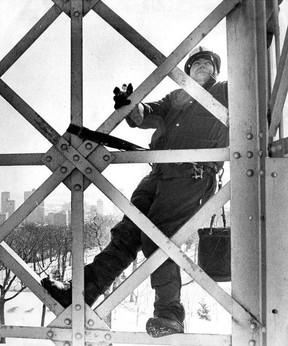

Incandescent bulbs were eliminated in 1992 when fibre-optic lighting was introduced during $305,000 in renovations. That meant workers would no longer have to climb up three or four times per year to replace bulbs.

In 2009, the city spent $1.9 million to upgrade the cross, opting for an LED lighting system.

Advertisement 6

Story continues below

Article content

The SSJB gave the cross to the City of Montreal in 1929, but the transfer in ownership was only formalized in 2004.

7. Drapeau wanted a new cross

Admired and derided for his grandiose ideas, Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau for years dreamed of building a huge tower on Mount Royal.

In March 1986, he envisaged a structure up to 100 storeys high, featuring a revolving restaurant, a disco, an observation deck for tourists and cable cars bringing visitors from ground level. It would incorporate the mountain’s radio and TV transmission tower.

Architects were also ordered to include a cross that would be visible from many kilometres away.

The Gazette’s editorial board pooh-poohed the idea of “erecting a massive, overarching symbol of a single religion, on a scale so gigantic as to dwarf Maisonneuve’s original cross.”

Drapeau announced his retirement as the tower was being planned. The idea was scrapped.

8. Some say it should go

In 2022, an Indigenous group unimpressed by an apology from Pope Francis over the Catholic Church’s role in residential schools said the mountain cross should come down.

Advertisement 7

Story continues below

Article content

“The cross reminds us of the horrors that we have lived and that we have survived,” said Kahentinetha, a member of the Mohawk Mothers, a group from Kahnawake. “It hurts us every time we see it because we know what happened.”

The place of Christian symbols in Quebec’s secular society came up in 2009 amid a debate over “reasonable accommodation” of non-Christians.

Salam Elmenyawi, head of the Muslim Council of Montreal, told The Gazette he had no problem with the cross on Mount Royal.

Rabbi Reuben Poupko agreed: “There are some times when a symbol that in its origins is purely religious takes on other connotations, and I think people can appreciate that.”

Tens years later, Quebec debated a secularism law aimed at ensuring the province maintained a neutral religious stance.

Mayor Valérie Plante took the crucifix down at city hall but said beloved landmarks associated with religion would remain. The mountain cross is “not a democratic institution where we make decisions,” she said.

9. Rumours of its removal swirled

In 2019, a dozen members of a group called “Guardians of Quebec” held a protest in front of the cross. They carried the flags of Quebec and of the Patriote rebels of the 1830s, as well as a large cross bearing a skeleton and a sign reading “Trudeau, traitor of Quebec.”

Advertisement 8

Story continues below

Article content

With no evidence, they were convinced “Québecophobic” McGill University was about to take over part of the mountain, including the cross, to put up condos.

“We don’t have any tangible proof, but we’ve heard about it from a lot of people,” organizer Luc Desjardins told Radio-Canada. “There’s never smoke without fire.”

10. Adding M and L to make MTL

The cross looks like a T, so why not add an M on one side and an L on the other?

That was the thinking of MBA student Philippe Mailhot, who proposed creating an MTL logo and leaving it that way for 375 days as part of the city’s 375th anniversary celebration in 2017.

Heritage Montreal called the idea unfeasible because it would have involved cutting trees and building a concrete structure.

The SSJB also wasn’t amused.

“The Mount Royal Cross is not a ‘T,’” said Maxime Laporte, the organization’s president. “Nor is it (today) a purely religious symbol. … The cross represents the beginnings and permanence of the French adventure in America.”

The Cross: By the numbers

- 33: Height in metres

- 10: Width in metres

- 26: Weight in tonnes

- 1,830: Pieces of metal

- 6,000: Rivets

- 80: Visibility in kilometres

Recommended from Editorial

Advertisement 9

Story continues below

Article content

Article content

Comments